Interactive Forum on Indigenous Knowledge

The Kapakan Interactive Forum on Indigenous Knowledge was held July 22-24, 2019 at the Kinawit cultural site of the Val-d’Or Native Friendship Centre. This event officially launched the activities of the Kapakan Alliance, an initiative for the coproduction and mobilization of knowledge on educational success and ways of learning in an Indigenous context. The Forum brought together approximately 60 people: representatives of Indigenous organizations, Indigenous scholars, academic researchers, students, and advisors of the Fondation Lucie et André Chagnon, all sharing an interest in education and the transmission of knowledge in an Indigenous context.

The objective of this Forum was to share experiences, teachings, expertise, and skills related to various modes of transmission of knowledge that exist in the Indigenous world. The event provided an opportunity to learn about principles, practices, initiatives, community projects, and collective actions based on taking this knowledge into consideration to document the keys to learning and educational success and better circumscribe their implementation in various fields of community, organizational or educational action.

Schedule of activities

As a response to the central objective, the Forum left much room during the first half-day for discussion among the participants, with the opportunity to introduce themselves, share the story of their journey, and state their personal and professional interests. Many moments of social and cultural exchanges were also experienced, especially through sharing of meals, collective preparation of a traditional feast, preparation of sweat lodges, production of crafts and artistic objects, and a traditional dance show.

Three thematic workshops which were held simultaneously provided an opportunity to reflect on the main scientific orientations of the Kapakan Alliance: 1) school, education, and the education system; 2) language and learning styles; 3) the role of the land in the transmission of knowledge.

Two Mexican delegations, especially invited for the event, shared their own experiences regarding Indigenous education. The first delegation was composed of members of the Centro de estudios para el desarrollo rural (CESDER), a nongovernmental community organization located in the State of Puebla and dedicated to the training of campesinos and Indigenous peoples from the region; CESDER is a long-standing partner of the DIALOG Network and of the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS). The second delegation, under the responsibility of Professor Dominique Raby, included two Indigenous students from Colegio de Michoacàn.

What [we] are doing today. It is the beginning [of] when we are coming together and share the knowledge, [as] brothers, sisters, nations.

Irene Bearskin-House, Cree Women of Eeyou Istchee Association

Thematic workshop: school, education, and the education system

This first workshop focused on the place the transmission of culture has in the standardized education system, as well as the consequences of the deployment of this system on Indigenous identity. Then, the discussion dealt with the favourable conditions conducive to the creation of safe learning environments, and the importance for schoolteachers and directors to develop culturally-safe practices for Indigenous students.

Cultural responsibility of education

For the participants in this workshop, the idea of education goes well beyond the structure of the school or the school system. The standardized education system has resulted in an identity and cultural disconnect by solely emphasizing formal instruction; in other words, the learning of notions and knowledge with little grounding in Indigenous cultures. This disconnect began with Indian residential schools whose impacts profoundly altered the markers of identity. Contrary to existing pedagogical approaches employed in formal education, as many people mentioned, culture is mostly acquired through observation and action.

Education starts when we are in the womb, and my turn came when I bore children. These learnings are very important. We learn by example.

Rose-Anna Niquay, Manawan

Other people shed light on the risks inherent to withdrawing the responsibility of the transmission of culture from the parents when such activities are only overseen by the school. Some Indigenous organizations have adopted strategies to limit this risk, while holding their cultural activities within a school framework. One participant mentioned that, in most cases, the separation of the responsibility between school instruction and culture is not as clear cut since the cultural activities taking place at school are encouraged by the teaching staff, the school environment, and the administration. Conversely, it is more difficult for the schools in the Québec network and the urban Indigenous community organizations to encourage the transmission of culture in the same way. Some examples of cultural activities included in a typical education framework were mentioned:

- The Centre d’amitié autochtone de Lanaudière built bridges with certain public schools in the city of Joliette to foster a culturally-safe environment for Indigenous students (for more information, see Cahier ODENA 2017-01);

- In the Anicinape community of Pikogan, the cultural activities take place at the Migwan School but are considered community activities;

- In the Atikamekw community of Manawan (as in many other communities), one full week is dedicated each year to traditional teaching on the land. During this time, school teaching is suspended to make room for cultural activities.

Safety and protection in the learning environment

Many participants said they were in favour of the implementation of new spaces, other than the school itself, to provide cultural transmission. Thus, a favourable condition for learning would be to provide safe spaces, including physical as well as educational and emotional safety, through the development of practices in harmony with Indigenous learning styles and social interaction. Some people denounced the fact that there was still a lot of abuse toward children, situations that have had impacts on educational journeys and learning. Residential schools contributed to this reality since they did not ensure children’s safety, by normalizing physical, psychological, and sexual violence, resulting in trauma that was subsequently passed on from generation to generation. Nowadays, there is a sense of urgency for communities to mobilize the youth, develop tools to ensure their well-being, and implement the recommendations of the national commissions such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission or the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

Cultural safety practices

There is an Indigenous cultural specificity in the way knowledge is transmitted. This difference should be expressed at school, in educational contents, in the teaching of language, and the way children are supervised. Again, one of the difficulties comes from the way Indigenous residential schools and then the western education system overlooked the Indigenous cultural elements of knowledge transmission. Non-Indigenous staff is usually not familiar with the importance of these elements that are closely related to each other. Moreover, there is not much room within the school system to translate these relationships into constructive educational strategies or practices. To showcase cultural activities and Indigenous values that strengthen students’ identities, the Migwan primary school (Pikogan) adopted values based on the seven traditional Anicinapek teachings. In this perspective, the standard school program, mostly built on individual learning, is combined with a significant collective dimension.

At school [Migwan], we follow the [provincial] program. However, there are always cultural activities. But that part is community-based. We went with three values – respect, belief in the child, pride – to give an identity back to our students.

Julie Mowatt, Pikogan

As for content, the Indigenous teaching staff tends to strengthen Indigenous identity though their teachings. Conversely, we notice that non-Indigenous staff encourage opening up to the world by relying on concepts which children find hard to relate to and that refer to other realities. Lengthy explanations are therefore necessary for these concepts which may entail delays in the learning process. Language is an additional source of difficulty since French or English are second languages for most Indigenous students. Furthermore, the majority of the teaching staff whose mother tongue is French or English speak very fast, which contributes even more to the delay in the assimilation of concepts by the children. For this reason, it is important to further support these teachers and to remind them of the importance of speaking more slowly and explaining each of the terms used. Finally, modes of knowledge transmission and the way children are monitored are also different between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. One participant observed that non-Indigenous teachers tend to intervene more sternly with the children, for example, by isolating them in the classroom if there is a problem. She explains that the preferred approach to dealing with behavioral issues in her community, is that teachers intervene more gently with students, by bringing them outside, explaining the situation without making them angry, and then bringing them back into class and making sure that they are not perceived as a troublesome child.

Many people who participated in the workshop denounced the fact that there is still a great lack of Indigenous teachers in communities; yet, theoretically, they are in a better position to create favourable learning environments for a successful educational journey. It is also pointed out that the staff going to work in the communities is very often quite young, with few qualifications, and rarely sensitive to Indigenous realities. Cultural training should be provided to future teachers during their bachelor’s degree, for example, through training modules where they would learn how to teach in an Indigenous context. To make up for this current situation, the Pikogan community has started to reflect on how to welcome non-Indigenous teachers and has implemented an awareness approach where they can learn about Indigenous history and specificities. This approach is part of a greater effort to create a school that represents Indigenous people rather than having a framework imposed upon them by administrators and public servants from outside the community.

Thematic workshop: language transmission

Participants in the second workshop were interested in the relationship between culture and language, reflected on the modes of Indigenous language transmission, and described initiatives implemented to enhance the teaching of language.

Culture and identity

Much like the discussions which took place in the first workshop, language was intricately linked to identity and was positioned as a symbol of resistance in the context of a minority culture. However, participants denounced the fact that their Indigenous languages were considered by the State as part of a bygone folklore and investments in their maintenance, transmission and revitalization are scarce. For the Mexican participants, Indigenous language is seen as a unifying element that contributes to cultural pride. Language also contributes to a better understanding of the environment and culture and ensures both collective continuity and the defence of the territory. However, the Spanish language is so widespread and easy to learn that many people will never learn their Indigenous language.

I have heard many Indigenous languages at this event which made me realize the diversity of languages. This is something beautiful that must be maintained. Each people or community must contribute to their children’s education. I would like to have the opportunity to express how lucky we are that this is the International Year of Indigenous Languages [UNESCO]. We are proud to be a part of it.

Margot Mowatt, Pikogan

It was also observed that there is a rupture in the transmission of language within the communities, whereas the older generation generally masters the language quite well, which is not so for the youth. This may be explained by the fact that learning the language is complex, but also because there is a loss of cultural pride and identity. Even if a lot of energy goes into Indigenous languages in school, at the same time, we must work on identity and pride at home.

Initiatives for the teaching and the protection of language

Societal changes, such as the decline in intergenerational relationships within families, or the prevalence of French or English in teaching, complicate the retention and transmission of language. Participants emphasized that a solid cultural foundation is essential for the acquisition of the cultural competencies for living together.

There is a problem in the way the teaching of Indigenous languages is integrated in the current programs of study. Many feel that we are at a critical moment where we must firmly engage in the preservation of Indigenous knowledge, at school as well as in the family. Various initiatives contributing to the teaching and transmission of Indigenous languages are already implemented.

- One of the participants learned his language at home when he was very young. He learned French with his father before 8 o’clock and then Innu with his mother after 8 o’clock. He finds it important to establish a structure and a favourable environment for learning and would like to use the same method with his grandchildren.

- The Abenakis (Waban-Aki) explain that their situation is different, where 90% of the population lives outside their territorial communities. Manuscripts, recordings, and documents exist, but there is no educational material. For this reason, one participant had personal letters translated, to have them in French and in Abenaki. Many efforts were invested in Odanak to regenerate the language. For example, street names and songs were translated into Abenaki. A non-Indigenous teacher learned the language and now contributes by teaching it. Speakers have attained quite a good level and are able to share on Facebook, but there is a perceived need to call upon outside expertise.

- For the Naskapis, the Band Council was consulted as far back as 1975 for the development of a learning curriculum for the Naskapi language. One of the participants contributed to the development of this curriculum and taught it for 43 years. The language is taught from pre-kindergarten to Grade 13, and all subjects are taught in Naskapi.

- In Mashteuiatsh, a web application was created to learn the Ilnu language. Conversation workshops are mandatory for employees of local administration and time is allocated in their work schedule to learn the language. It was possible to integrate the language at school with the approval of the Ministère de l’Éducation. There are also bilingual newspapers and social media (Ilnu-French), but it is hard to know if people read them. It is important to create directories of cultural knowledge, through radio and videos, because this is what really resonates with people.

- At CESDER, there is a program for the protection of the Nahuatl language that contributes to the battle against oppression, and the transmission of the language and culture to the young generations.

Thematic workshop: the territory as a place of knowledge transmission

In the third workshop, participants explored the relationship between the land and the transmission of knowledge. Territorial dispossession which resulted in loss of language and culture was identified as the main element in the issues associated with the transmission of knowledge in the Indigenous context. The participants proposed many avenues for reflection to recenter the land in view of promoting and supporting educational transformation.

Territory, language, culture

As an active component of social organization, the territory is considered a privileged place of learning and a source of knowledge; this is where each person gains their cultural capital. The territory is the cornerstone of language and culture developed and preserved through the relationship that Indigenous people maintain with land and nature (composed of animate and inanimate beings). This relationship expresses itself more clearly in Indigenous toponomy which contributes to the transmission of information about traditional hunting and fishing territories, family and clan genealogies, significant historical events, and ancestral routes (history of mobility), to name a few examples.

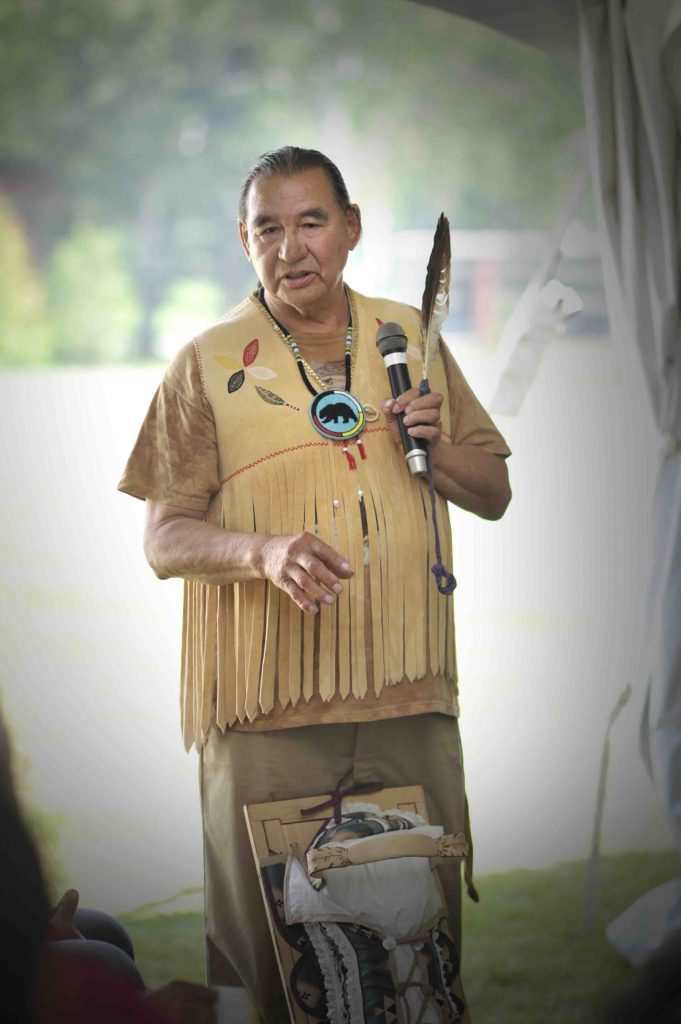

Education is very very important. We are all teachers. Even that little child. Some of us, we study to teach, in the institution. And the traditional knowledge of the world tells us learning and healing is one. We come in this earth to learn and to teach each other. We forgot that. Learning and healing never ends. We are born to learn and as we learn we are healing ourselves and it doesn’t end until we leave. It never ends.

Larry House, Chisasibi

As an anchor for history and memory, the land plays a primary role in transmission, regeneration, and knowledge mobilization. Today, youth spend most of their time at school, « enclosed within four walls », whereas in the past, teaching and transmission of knowledge took place on the land, as an extended family. Thus, the land is the foundation of culturally anchored education and modes of intergenerational transmission that use Indigenous language and are based on Indigenous cultural principles and values that generate a sense of belonging and an individual and collective identity.

Deterritorialization of knowledge

The participants recalled how mapping, servicing the colonial project, historically deterritorialized and marginalized Indigenous Peoples to make room for companies exploiting resources. This loss of territory, in turn, weakened the authority of the knowledge keepers and that of the leaders, undermined Indigenous knowledge, and invalidated the family responsibility regarding the education of their children. Many recognized the continuation of colonial structures and configurations in the contemporary neo-liberal system, as the extraction industry supported by the State perpetuates not only economic dominance but also diverts the initial meaning of territory. Many examples dealt with the issues of contemporary territorial dispossession that is based on the negation of Indigenous knowledge concerning the environment. Women are particularly more disadvantaged in territorial governance following the imposition of an absolute patriarchy through the Indian Act.

Many people emphasized the emotional and relational consequences of territorial alienation, entailing not only loss of language and culture, but also affecting individual and collective well-being (mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual). Some participants explained how the sharing of territorial jurisdiction affects « the feeling of having your own home »: life on the reserve/in the community is considered as « belonging to the federal », being in the city or « on the highway » is under provincial authority, and the ancestral territory constitutes the only space where individuals feel fully Indigenous. Thus, forced sedentarization, residential schools, imposition of laws and policies for the purposes of assimilation altered the way territory was imagined, felt, designed, and used. Therefore, it is important to consider a renewed mobilization of knowledge, in harmony with Indigenous aspirations and priorities, to contribute to the transformation of education in general.

Elements of a transformational process in education

A first element of an educational transformation would be the recognition of the interdependence between the territory and knowledge which seems to be vital for the transmission of knowledge and cultural continuity. As many participants mentioned, decolonisation and social reconstruction require the establishment of interpersonal, intragenerational, and intergenerational relationships; manifestations that require the reappropriation of territories and the regeneration of knowledge and culture relevant to each group.

We cannot prepare children for the future if they are not prepared for the present, if they don’t have the skills to live with dignity today.

Alejandro Marreros Lobato, CESDER

Reconnecting with the land, and therefore the regeneration of knowledge systems, should contribute to recentering Indigenous values, principles, and pratices in the educational realm. The restoration of ethical relations to guide the responses to contemporary realities constitute a second element of the transformation desired. Often expressed through the image of a constellation of responsibilities and obligations, these ethical relations ensure collective and cultural continuity by focusing on the central role of knowledge holders, respect for diversity, consideration for individuals’ relational capacities, and the protection of Indigenous social structures.

Some people clearly expressed it: « to learn is to defend ». By reenforcing the Indigenous social structures that prioritize and value an approach that is self-directed and self-governed by the group, we can envision a collective action working toward the social, political, and cultural transformation of Indigenous societies. Ultimately, the reterritorialization of learning will contribute to strengthening identity and create favourable conditions for the affirmation of the rights of Indigenous Peoples.

CESDER educational strategies

The Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Rural (CESDER) is a non-governmental organizations founded in 1982 in the Nahuatl de San Andrés Yauitalpan community, north of the State of Puebla (Mexico). Among many initiatives, the CESDER offers a bachelor’s and a master’s program through an approach based on cooperative education. The institution offers its teachings in the classrooms but also in the communities, and maintains a dual mission combining education and social innovation.

Dialogue of knowledge

The first educational strategy employed by CESDER is to showcase knowledge and ways of learning that students already hold. By pooling their knowledge, the complementarities can be identified and then strengthened. This learning strategy is achieved through a better knowledge of the land and culture. CESDER encourages students to integrate daily life in their respective communities: observation of celebrations and ceremonies, sharing sessions with elders, documenting stories and legends, or learning the language.

It is also important to alternate between practical exercises and scholarly work in the curricula. The students don’t spend all day reading or listening to a teacher. It is important to work in the gardens, raise pigs and rabbits, contribute to reforestation, and grow vegetables. By combining practice and theory, it is possible to match concrete content with academic concepts.

Cooperative education

CESDER was designed as a space for collaborative expression, in which students are part of a learning community and take charge of their own educational journey. All the CESDER programs are designed to allow students to meet once a month, from Sunday to Saturday, on the same site where they live together at a hostel that they share with about 80 people. Each of them has a guide to direct the work to be done on the CESDER site itself, but also for when they go back to their communities of origin. At the hostel, the students learn to live as a collectivity, share knowledge, and participate in the activities necessary for the site operations and subsistence of the group as a whole. The hostel is a quite simple place that does not look like the big universities but is conducive to the achievement of the centre’s educational mission.

Sometimes, even when communities are close to each other, there is not much contact between them, so the existence of the hostel contributes to the creation of new relations and the acquisition of new skills. For example, it is possible for men to learn roles that would usually be set apart for women and vice-versa. It is also a place where learning about living together and becoming more autonomous are encouraged since the students must fulfil many responsibilities. When certain people do not abide by the rules, the group decides which measures will be implemented to rectify the situation. This mode of operating also contributes to the preservation of the Indigenous student’s dignity since they are not subject to a predetermined program; rather, they have the possibility of progressively designing their own learning process.

Student research at the Colegio de Michoacán

Two Indigenous students from the Colegio de Michoacán also participated in the Forum and had the opportunity to present their master’s research.

Fatima Gregorio Cipriano : Impacts of the kaxumpikua for the Purépecha women

Fatima is a Purépecha student pursuing a master’s degree in anthropology. Her projects aims to understand what it means to be a present-day youth, however, without rejecting the role and place of elders.

At the core of her reflection, she places the concept of kaxumpikua, « must-be », which means to behave in an exemplary way and know how to act in Indigenous rituals and life-styles. The elders in her community say that the youth are no longer kaxumpikua. A concrete manifestation of this problematic is that women hardly marry anymore. Traditionally, the age of marriage for women was between the 15 and 20 years old but today, they are questioning themselves in relation to this reality and on its consequences in the areas of sexuality, status, and autonomy. To explore the subject, Fatima conducted interviews with Purépecha women. Many women interviewed said that they liked traditions, but they weren’t comfortable with the obligation of getting married so young. Many of them even prefer to leave the community.

Eleazar Valle Pineda : reclaiming the Hñähñu cultural capital

Eleazar is a Hñähñu student pursuing a master’s degree in anthropology. He is interested in socialization strategies for Indigenous students in an academic setting and in the opportunities offered by research to support community initiatives for cultural and linguistic affirmation.

Extremely critical of the Mexican school system that he considers to be disconnected and that it offers teaching without context, he mentions having been raised in conditions that were not very favourable for learning: in a solitary fashion, in a poor family, and hating school. When he began to study anthropology, he wondered how people such as himself, with no cultural capital, can persevere in their studies. He observed that people from his community sometimes had gaps in their academic planning but that they learned from their life in society. These people create other socialization strategies for themselves. For this reason, his own master’s project is based on a advocacy perspective. With colleagues from different Indigenous groups in Mexico, he employs ethnographic discussions to understand how each person can regain certain elements of their culture and community, position themselves as being Indigenous, and contest colonial institutions: we are here, we are staying here, and we have nowhere else to go.

Cultural sharing sessions

Several cultural sharing activities were organized during the Forum. The group of drummers and traditional dancers, Screaming Eagles from Pikogan, demonstrated dances and songs. Denis Vollant (Innu from Uashat) and Charles-Api Bellefleur (Innu from La Romaine) presented a workshop on the Innu traditional drum and songs. Carine Valin and Jean-Pierre Verreault, Ilnu from Mashteuiatsh, prepared traditional meals and medicinal beverages. Anicinabe traditional artist, Alexis Weizineau produced many handicrafts onsite. Abenaki youth Charlotte Gauthier-Nolett and Pierre-Alexandre Thompson presented the Niona project, an initiative for the production and broadcasting of the Abenaki culture through new technologies. Fatima Gregorio Cipriano presented Purépecha traditional clothing from her region. The bannock-making session organized by Denis Vollant was an opportunity to reflect on the learning of fundamental being in relation in Indigenous cultures: patience, listening, respect, and mutual assistance.

From Mexico to Canada, Montréal to Kawawachikamach, Pikogan to Pessamit, the issues of transmission and mobilization of Indigenous knowledge in the education system show to what extent school has shifted away from Indigenous cultures. Linked to the colonial history of North and South America, this shift is still felt today in educational programs, in classical western pedagogy, as well as in the isolation of students in their ancestral and family territories. While the colonization processes from north to south and south to north took multiple forms, participants in the Kapakan Interactive Forum on Indigenous knowledge identified some leitmotifs, such as the loss of Indigenous languages, the weakening of intergenerational relations, and the deresponsibilization of communities regarding their children’s education.

You can only teach what you know. If you don’t know the culture, you can’t really teach it. It requires other measures and they must be defined with the people. The way in which teaching takes place must be done with elders; they must be involved in the teaching.

Carole Lévesque, INRS

If, over time, school has become a space of alienation, other spaces and learning environments have been established in Indigenous territorial communities where the primary function of the transmission of knowledge is to reinstate social relationships, preserve culture, and revive identity and the sense of belonging. By using both formal and informal modes of education, these multiple Indigenous initiatives are based on a comprehensive and broad vision of educational success, including life-long educational success, and focuses on individual and collective well-being and living a good life. Consequently, the mobilisation of knowledge anchored in cultural values could provide answers to contemporary priorities, open new avenues for action and solidarity among Indigenous Peoples on the one hand, and between Indigenous and non-Indigenous societies on the other, in a spirit of reconciliation and cultural equity.

The July 2019 gathering allowed us to realize that Indigenous culture is still active in the universe of those who are part of the First Nations of Québec and of the young Indigenous individuals from Mexico. This realization leads us to believe that there is a set of links between us in ways of acting, thinking, or sharing. In light of this situation, our hope is to continue to preserve the culture.

Margot Mowatt, Pikogan

A big thank you to all the participants: Suzy Basile, Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue; Irene Bearskin House, Cree Women of Eeyou Istchee Association; Charles-Api Bellefleur, La Romaine; Diane Caouette, Translator; Chaffee Judith, CESDER; Catherine Charest, Regroupement des centres d’amitié autochtones du Québec; Édith Cloutier, Centre d’amitié autochtone de Val-d’Or; Beverly Cox, Chisasibi; Nancy Crépeau, University of Ottawa; Laurence Desmarais, INRS; Marie-Ève Drouin-Girard, Interpreter; Yvon Dubuc, Montréal; Noat Einish, Naskapi Development Corporation; Justine Gagnon, Victoria University; Fatima Gregorio Cipriano, El Colegio de Michoacán; Asunciona Hernández Rosales, CESDER; Eric House, Chisasibi; Larry House, Chisasibi; Francis Ishpatau, Tshakapesh; Alice Jérôme, Pikogan; Oscar Kistabish, Centre d’amitié autochtone de Val-d’Or; Jocelyne Kistabish-Thomé, Matagami; Jacques Kurtness, Mashteuiatsh; Mario Labbé, Kinawit; Roxane Labbé, Kinawit; Florent Laperrière, Université de Fribourg; Élisha Laprise, Fondation Lucie et André Chagnon; Carole Lévesque, INRS; Marielle Lévesque, Communidée-Services alimentaires; Renée Lévesque, Communidée-Services alimentaires; Stephan Maillot, Technician; Rose Mapachee, Pikogan; Tom Mapachee, Pikogan; Alejandro Marreros Lobato, CESDER; Agnes McKenzie, Naskapi Development Corporation; Andrea McLeod, Cree Women of Eeyou Istchee Association; Viviane Michel, Femmes Autochtones du Québec; Julie Mowatt, École Migwan; Margot Mowatt, Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue; Natasha Blanchet-Cohen, Concordia University; Rose-Anna Niquay, Manawan; Charlotte Nolett, Odanak; Hélène O’Bomsawin, Alma; Nicole O’Bomsawin, Odanak; Amelia Orellana, Interpreter; Eddy Pashagumskum, Chisasibi; Emmanuelle Piedboeuf, INRS; Magalie Quintal-Marineau, INRS; Thérèse Quitich, Manawan; Dominique Raby, El Colegio de Michoacán; Ioana Radu, INRS; Luc Robitaille, Technician; Patricia Rossi, Fondation Lucie et André Chagnon; Ignacia Serrano Arroyo, CESDER; Hélène St-Onge, Pessamit; Doris St-Pierre, Translator; Pierre Alexandre Thompson, Odanak; Nathalie Tran, INRS; Marie Tshernish, Tshakapesh; Carine Valin, Mashteuiatsh; Eleazar Valle Pineda, El Colegio de Michoacán; Jean-Pierre Verreault, Mashteuiatsh; Denis Vollant, Uashat.